Concept of Citation Indexing:

A Unique and Innovative Tool

for Navigating the Research Literaturespeech presented

at

Far Eastern State University

Vladivostok - September 4, 1997by

EUGENE GARFIELDChairman Emeritus,

Institute for Scientific Information®Publisher,

The Scientist®

3501 Market Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA

Tel. 215-243-2205

Fax 215-387-1266email: garfield@codex.cis.upenn.edu

Home Page: http://garfield.library.upenn.edu

By the references they cite, authors make explicit linkages between their current research and prior work stored in the vast archive of the scientific literature. Citations symbolize the concepts or scientific ideas authors discuss. These conceptual associations by citation have been described by Robert K. Merton,1Manfred Kochen,2 and other scholars as intellectual transactions, formal acknowledgments of "intellectual debt" to earlier authors. Explicit references imply that an author has found a particular published theory, method, or datum useful in some way.

ISI's citation-based databases index these intellectual transactions by tagging and listing both the cited and citing works. These reference-citation pairs can be described in many ways. The cited work (reference) is a paper or book that has been mentioned in the bibliography or footnotes of a citing work (source). The source work contains the cited references. Citation indexes were designed to facilitate information retrieval and dissemination using these source-reference connections. As a consequence, the ISI databases enable you to navigate the literature in unique ways. You are able to locate related papers independent of language, nomenclature, title words, or author key words. Citation-based search strategies include simple cited-reference searches, reference cycling, co-citation, and bibliographic coupling, that is linking of related papers through shared references (Related Records®). These cited reference strategies can be combined with a variety of key word, author, and institutional searches.

Unique Advantages of Citation Indexes

The ISI® databases differ from traditional indexing and abstracting services in several other ways as well. From the outset, the Science Citation Index® (SCI®), Social Sciences Citation Index® (SSCI®), and Arts & Humanities Citation Index® (A&HCI®) have been multidisciplinary. They cover virtually all disciplines whereas traditional services are limited to a single field or discipline. In this latter respect, VINITI abstracting in Moscow has also been multi-disciplinary. But it still does not produce a single unified index.

The advantages of a multidisciplinary index can be exemplified by the work of the Nobel Prize chemist Harold C. Urey. His now classic paper, published in Science3 in 1962, "Lifelike forms in meteorites" described the chemical compounds contained in meteorites that were essential to the formation of life. The first slide is a reproduction of an advertisement for the 1966 Science Citation Index which demonstrates its multi-disciplinary coverage in biology, cosmology, chemistry, earth sciences, geochemistry, and so on.

FIGURE #1 : HOW TO SEARCH

ISI's indexes are also comprehensive, providing complete coverage of all types of published source items--not just original research papers, review articles, and technical notes but also letters, editorial, corrections and retractions. ISI studies have shown that these latter items are important sometimes, have substantial impact, and provide useful links to controversial scientific issues. And they are not always indexed elsewhere.

The next slide shows a small sample from the 1997 Science Citation Index.

FIGURE #2: CITATION INDEX EXAMPLE

The citation index has the unique chronological ability to facilitate prospective as well as retrospective searches. As in traditional indexes, you can look backward to locate earlier papers. And you can go forward to determine who has cited an earlier work. By starting with a single paper or book, you can identify additional papers that have referred to it. And each retrieved paper, in turn, may provide a new list of references with which to continue the citation search. Thus, one may cycle backwards and forwards through several generations of related records.

Authoritative, Timely, In-Depth Access to the Literature

It is important to stress that the citation-based associations and connections within the literature are made by authors themselves. Traditional indexes typically rely on subject specialists using controlled vocabularies or thesauri. An example would be Medline, which is now a free service of the U.S. government. My first assignment as a researcher in 1951 was to work on the improvement of Medline subject heading lists(MeSH). To illustrate their shortcomings, consider my first experiment with citation indexes in 1954. Using the Index Medicus subject heading "adaptation," I tried to compile a list of references on Han Selye�s "general adaptation syndrome." From 1949 to 1954, 23 papers covered in Index Medicus had cited Selye's primordial work,4 but not one was indexed under "Adaptation." (This search was suggested by a medical librarian, Erich Meyerhoff at Columbia University Medical School.)

Another shortcoming of human indexing is the inevitable delay due to the time required to read the papers to make subjective judgments and select relevant headings or descriptors. To this day, Medline�s timeliness is reduced because of this delay. There is also a significant labor cost. In contrast, ISI�s citation indexing computer-enhanced algorithmic system permits the SCI, SSCI, and A&HCI to be virtually concurrent with the literature. This does not mean there is no human intervention, but it is at a different level which focuses on standardization of inputs.

Citations as Indexing Statements in Review Articles

Thanks to a suggestion by Pharmacologist-Historian Chauncey Leake in 1951, I conducted a thorough analysis of review articles and their cited references. By doing what today would be called "content analysis," I soon discovered that the sentences in review articles were actually detailed, descriptive indexing statements about the papers or books they cited.

KEYWORDS PLUS

Even before citation indexes existed, these basic notion were further developed by Robert L. Hayne and myself in 1954 when I was a consultant to the pharmaceutical company now called Smith, Kline and Beecham. Through large test samples, we concluded that the titles of papers cited in reviews and other articles could be used to provide descriptive terms to "automatically" index the source papers. This was later confirmed in studies by A. J. Harley5, as Irv Sher and I reported6when KeyWords Plus was introduced in 1990. We called this derivative (algorithmic) subject indexing. Title words, author-supplied key words, and/or words in abstracts are supplemented by KeyWords Plus. These supplementary indexing terms are derived from the titles of papers cited in each new source document.

Incidentally, only about 30% of published papers contain author supplied key words. A larger percent contain abstracts. It would be helpful if all Russian journals provided both author key words and English abstracts.

SCI Search Strategies

There are at least four basic ways to search the printed and electronic SCI. Most searches begin with the Citation Index section, which is arranged alphabetically by the first author of the cited work. All publications cited during the designated indexing period are listed under the first author's name, just as they appear in the journals. In new versions of the SCI, all authors are indexed even in the Citation Index.

The Citation Index is itself often described as a massive author index. By now millions of papers and books have been cited.

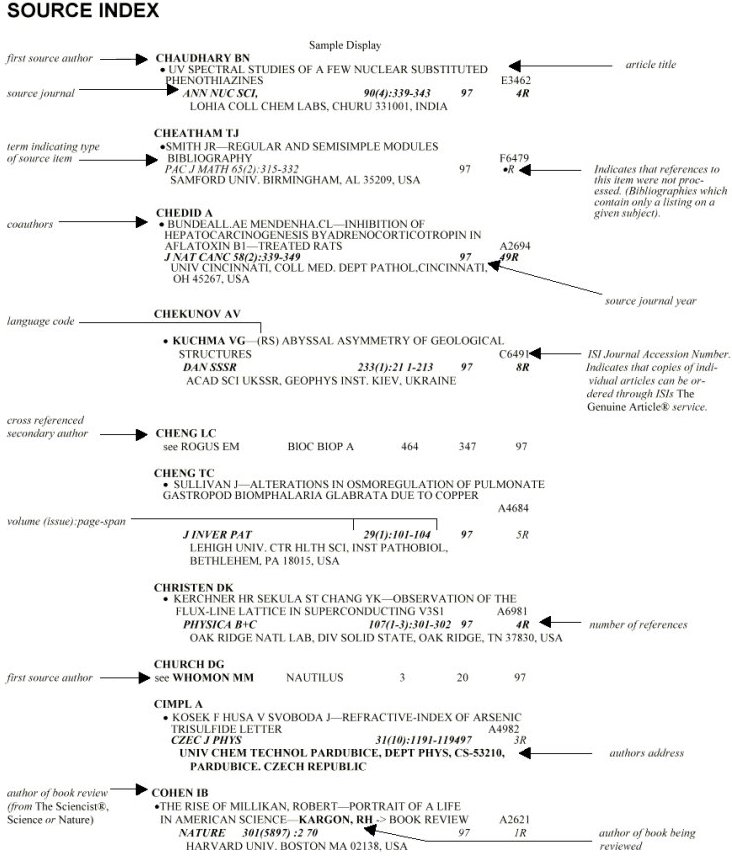

But SCI also contains a master Source Index in which all authors of articles indexed by ISI are recorded. This index also lists the full title of each paper. You use the Source Index to find out what an author has published. In the electronic version of the Source Index, the entry also includes a list of all other papers cited in each source article, as well as an abstract. It also permits you to find a series of related articles which I will explain later.

FIGURE #3: SOURCE INDEX EXAMPLE

To research a topic by title word or subject, use the Permuterm® Subject Index (PSI). The PSI is often called a natural language index. In the CD-ROM and electronic versions, ISI has augmented the subject heading capability through SCI's KeyWords Plus, as explained earlier.

FIGURE #4: PERMUTERM SUBJECT INDEX EXAMPLE The geographic institutional Corporate Index identifies papers published at a specific institution. The printed listings are organized both alphabetically and geographically. So it is possible to locate papers from a city or institution even if one does not know the names of authors. This is how you can identify authors from those locations.

FIGURE #5: CORPORATE INDEX EXAMPLE All of these indexing approaches can be combined when using the on-line and CD-ROM versions to find, for example, the papers that are published on a given topic at a particular university or company. These are referred to as boolean searches, that is combinations of indexing sets. These possibilities will be shown in the live demonstration that will follow my talk.

The Search Query

Textbook descriptions of searching tend to idealize the searchingenvironment. In reality, most scientists start a search without developinga formalized search query. In spite of the maxim that "fools rush in where angels fear to tread," this will, in fact, often produce useful results. In one way or another, you will find your way into the relevant citation pathway. If you visualize the literature as one gigantic topological network, with each published paper as a node, you are simply traversing the network.

Slide #6 shows the citaiton interconnections for 28 papers on DNA published from 1958 to 1967.

FIGURE #6: CITATION NETWORK OF EARLY DNA ARTICLES, 1958 to 1967

A similar map is shown for research on io transport papers from 1954 to 1970.

FIGURE #7: CITATION NETWORK OF ARTICLES ABOUT

"PERTURBATION OF ION TRANSPORT," 1954 to 1970

Verification

Many researchers follow the example of Nobel laureate Sir Peter Medawar who chose to ignore the literature until after the initial phase of laboratory exploration was over. In that case, the literature search is done when the research paper is being prepared for submission to a journal. Such researchers will begin to document the paper by recalling--essentially from memory--a dozen or so papers that are relevant to the background of the putative paper. Even for this process of information recovery, unless the researcher has stored reprints of the to-be-cited papers, indexes need to be consulted for verification.

Verification is a very significant part of the intermediary's work -- many researchers routinely submit their bibliographies to librarians to assure that the references cited are accurate. As the literature amply demonstrates, this practice is far from universal.7 The number of minor errors in literature references is shocking and a growing number of editors demand that the cited papers themselves are provided to check for accuracy.

Many journal editors would argue that the text of any reference cited should be consulted in the original. But that does not always occur. The SCI with Abstracts may be a compromise. And depending upon the field, other sources of abstracts are also available if the original is not in the library including Referatvnyi Zhurnali.

In the near future world of electronic access, it is expected that increasing percentages of the literature will be accessed electronically. In the next few slides, you see an example from ISI�s new Web of Science.

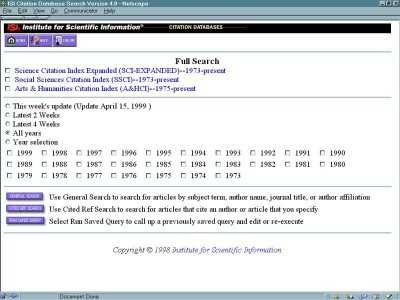

FIGURE #8 WEB OF SCIENCE

FULL SEARCH INTRODUCTORY PAGE

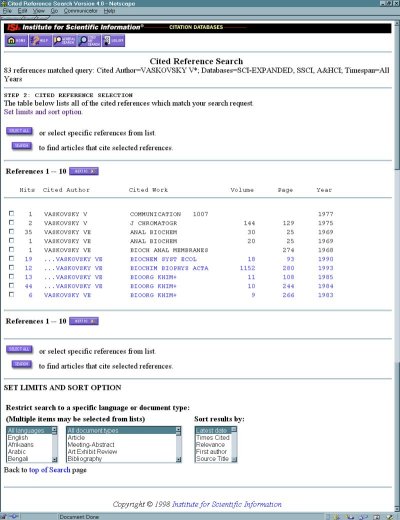

FIGURE #9 WEB OF SCIENCE

CITED REFERENCE SEARCH ON VASKOVSKY-V*The ISI databases are already available on-line through various vendors but now it is possible to access them via the Web of Science. This is the new Intranet and Internet version of the ISI databases. Ideally, every searcher would check the Web of Science to determine whether the references they have used have been cited in more recent papers that which may have modified the earlier experimental results or methods.

Citation Frequency Distribution

Actually, except for the few hundred papers that have been cited 1,000 times or more since their publication, most papers (including methods) are cited only a few times each year. Indeed, if you use an older paper that has been rarely cited, there is all the more reason to look for the most recent citing work.

The next slide show frequency data for 1945-88. Less than 300 papers were cited over 1,000 times up until 1988.

FIGURE #10: 1945-88

In Slide 11, we have data for 1955-87.

FIGURE #11: CITATION FREQUENCY 1955-87 SCI

Slide 12 shows data for 1987 alone.

FIGURE #12: CITATION FREQUENCY 1987 SCI

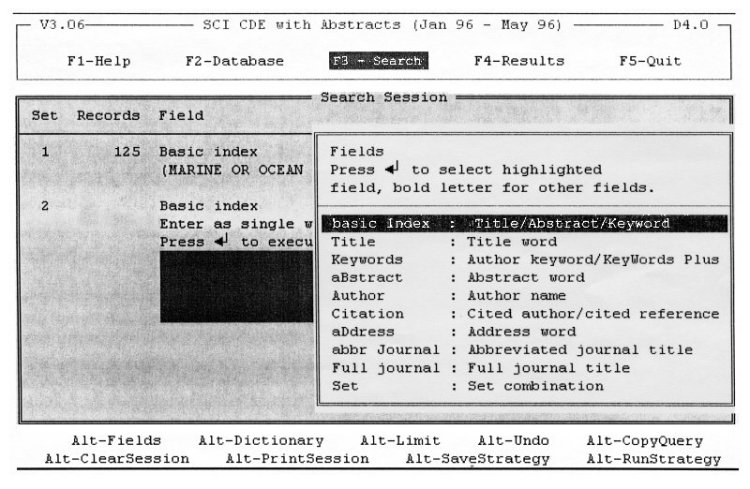

SCI CD-ROM

In the SCI Compact Disc Edition with abstracts -- the Basic Index mode combines four types of term indexing: title word, author keyword, KeyWords Plus, and abstract text. However, each can also be used separately.

FIGURE #13: SCI CD-ROM EXAMPLE

If you are searching a large field of literature, you may want to begin by limiting your search to Russian language articles or to review papers. When foreign language articles are identified, it is always helpful to scan the abstract before examining the full text in the library. It is unfortunate how often Russian language papers do not include English abstracts.

Impact Factor

Some of you may be aware that several years ago the Soros Foundation used citation data to make decisions about grants to Russian scientists. One of the criteria used in the selection process was the impact factor of the journals in which the candidate published. So I would like to briefly describe the impact factor. The current impact factor was designed to enable ISI to compare small journals to large journals. We did not want to rely solely on journal size.

In these two slides, we show the most productive and most-cited journals.

Here are the top 50 journals in those two categories.

FIGURE #14: MOST-PRODUCTIVE JOURNALS, 1974 AND 1989

FIGURE #15: MOST-CITED JOURNALS, 1974 AND 1989

On the other hand, if you divide total citations by articles published, you obtain the average number of citations per published paper. That is, the impact factor.

In slide #16, we show the top journals by impact. However, you can compute an impact factor for many different time periods. If you limit data to the most recent year, you obtain an impact factor which we call immediacy. This favors journals which publish currently hot material as e.g. Nature, etc.

FIGURE #16: JOURNALS RANKED BY CURRENT IMPACT

FIGURE #17: JOURNALS RANKED BY IMMEDIACY

Based on studies we did in the 60s, we determined that for evaluating journals for CC the best time period would be the two years prior to the current year for citations. So ISI�s current impact is based on 1997 citations to papers published in 1996 and 1995.

However, we also know that there are many differences in citation dynamics across fields. So impact factors should only be considered in terms of the category involved. Then within each category, we obtain a ranking of journals. ISI has established several hundred subject categories but one can create new categories by using the Journal Citation Reports® which give inter-citation activity between the 8,000 journals in the ISI database.

FIGURE #18: CUMULATIVE VS CURRENT IMPACT - Marine Biology Many scientists feel that the current impact factor is biased against smaller, slow-moving fields like marine biology, mathematics, etc. What happens if you take into account long-term cumulative citation data. Some journals seem to do better based upon a 15-year cumulation of data. But the question is whether this affects their ranking within the appropriate category. The slide demonstrates that this can be true.

The next two slides present data I�ve not yet published which demonstrate the effect of calculating 7-year and 15-year cumulative impact factors. I�ve shown the rank of each journal by cumulative impact and also the corresponding rank by current impact. This demonstrates that there can be significant changes when taking into account long-term cumulated data.

|

|

|

Cum Cities |

Source Items |

Impact Factor |

Rank |

| 1 | CELL |

|

|

|

|

| 2 | N ENG J MED |

|

|

|

|

| 3 | SCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

| 4 | NATURE |

|

|

|

|

| 5 | J EXP MED |

|

|

|

|

| 6 | EMBO J |

|

|

|

|

| 7 | FED PROC |

|

|

|

|

| 8 | J CELL BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 9 | P NAS USA |

|

|

|

|

| 10 | ARCH G PSYCH |

|

|

|

|

| 11 | J CLIN INV |

|

|

|

|

| 12 | LANCET |

|

|

|

|

| 13 | ANN INT MED |

|

|

|

|

| 14 | MOL CELL BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 15 | J NEUROSCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

| 16 | BLOOD |

|

|

|

|

| 17 | J IMMUNOL |

|

|

|

|

| 18 | J BIOL CHEM |

|

|

|

|

| 19 | CIRCULATION |

|

|

|

|

| 20 | J NAT CANCERINST |

|

|

|

|

| 21 | PHYS REV L |

|

|

|

|

| 22 | AM J HU GEN |

|

|

|

|

| 23 | J MOL BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 24 | AM J PATH |

|

|

|

|

| 25 | J VIROLOGY |

|

|

|

|

| 26 | CIRCUL RES |

|

|

|

|

| 27 | ANN NEUROL |

|

|

|

|

| 28 | MOLEC PHARM |

|

|

|

|

| 29 | J GEN PHYSIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 30 | ASTROPH J SUPP |

|

|

|

|

| 31 | EUR J IMMUN |

|

|

|

|

| 32 | CANCER RES |

|

|

|

|

| 33 | BIOCHEM |

|

|

|

|

| 34 | J PHYSL LON |

|

|

|

|

| 35 | HYPERTENSION |

|

|

|

|

| 36 | J INFEC DIS |

|

|

|

|

| 37 | ENDOCRINOL |

|

|

|

|

| 38 | LAB INV |

|

|

|

|

| 39 | J NEUROPHYSL |

|

|

|

|

| 40 | AM J PSYCHI |

|

|

|

|

| 41 | J AM CHEM SOC |

|

|

|

|

| 42 | ARTH RHEUM |

|

|

|

|

| 43 | DIABETES |

|

|

|

|

| 44 | GENETICS |

|

|

|

|

| 45 | GASTROENTY |

|

|

|

|

| 46 | NEUROSCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

| 47 | DEVELOP BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 48 | J COMP NEUROL |

|

|

|

|

| 49 | AM REV RESP DIS |

|

|

|

|

| 50 | BR J PHARM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cum Cities |

Source Items |

Impact Factor |

Rank |

| 1 | CELL |

|

|

|

|

| 2 | N ENG J MED |

|

|

|

|

| 3 | J EXP MED |

|

|

|

|

| 4 | J CELL BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 5 | P NAS USA |

|

|

|

|

| 6 | ARCH G PSYCH |

|

|

|

|

| 7 | J CLIN INV |

|

|

|

|

| 8 | NATURE |

|

|

|

|

| 10 | SCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

| 11 | MOL CELL BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 12 | J NEUROSCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

| 13 | EMBO J |

|

|

|

|

| 14 | CIRCUL RES |

|

|

|

|

| 15 | NEUROSCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

| 16 | ANN INT MED |

|

|

|

|

| 17 | J HIST CYTO |

|

|

|

|

| 18 | NUCL ACID RES |

|

|

|

|

| 19 | J GEN PHYSIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 20 | J COMP NEUROL |

|

|

|

|

| 21 | J IMMUNOL |

|

|

|

|

| 22 | J BIOL CHEM |

|

|

|

|

| 23 | ASTROPH J SUPP |

|

|

|

|

| 24 | BLOOD |

|

|

|

|

| 25 | CIRCULATION |

|

|

|

|

| 26 | J NEURPHYSL |

|

|

|

|

| 27 | LANCET |

|

|

|

|

| 28 | HEPATOLOGY |

|

|

|

|

| 29 | GASTROENTY |

|

|

|

|

| 30 | AM J MED |

|

|

|

|

| 31 | J PHYSL LON |

|

|

|

|

| 32 | DIABETES |

|

|

|

|

| 33 | PHYS REV L |

|

|

|

|

| 34 | LAB INV |

|

|

|

|

| 35 | ANALYT BIOC |

|

|

|

|

| 36 | GENE |

|

|

|

|

| 37 | AM J CARD |

|

|

|

|

| 38 | J MOL EVOL |

|

|

|

|

| 39 | ANN NEUROL |

|

|

|

|

| 40 | GEOCH COS ACTA |

|

|

|

|

| 41 | J AM CHEM SOC |

|

|

|

|

| 42 | PFLUG ARCH |

|

|

|

|

| 43 | EUR J IMMUN |

|

|

|

|

| 44 | J LIPID RES |

|

|

|

|

| 45 | MOLEC PHARM |

|

|

|

|

| 46 | ECOLOGY |

|

|

|

|

| 47 | J CLIN ENDOCRIN |

|

|

|

|

| 48 | J MEMBR BIOL |

|

|

|

|

| 49 | AM J PATH |

|

|

|

|

Citation Consciousness

It is a truism which needs to be restated for each generation that scientists should get into the habit of literature searching. This habit or practice is by no means universal. One of the more obvious reasons to conduct searches is to avoid the unwitting duplication of research and prevent wasted time and effort. Classic studies have demonstrated a remarkable amount of unintentional duplication sometimes even within large institutions.

Editors should expect authors to follow "due diligence" standards required of inventors in seeking patents. Authors should formally assert and verify that their ideas are original. Authors should be required to acknowledge the "prior art" that directly or indirectly influenced their research. The most directly relevant papers should be explicitly cited and a record of the databases and terms searched should appear in lab notebooks.

The problem begins with teaching. Too few universities requirethat students learn how to search the literature. But with proper mentoring, university graduates should be conditioned to search the literature and practice these techniques throughout their careers.

Citation as the Universal Language of Communication

References are found at the end of most research articles. In someliterature, especially in the social sciences and humanities, they may occur in footnotes. In a classic study, Saul Herner found that a major impetus for the papers scientists seek in libraries were the references cited in recent papers. Conferences and personal contact are also important sources of references for scientists. They supplement leads found in the primary literature.

Referencing has often been described as a language of scholarly communication, as described recently by Paul Wouters at the Sixth International Conference for Scientometrics and Infometrics in Jerusalem.8 Time does not permit me to discuss these aspects of citationology as well as citation behavior. Last year I discussed "When to Cite" in Library Quarterly9 and listed about 15 categories of citation:

|

|

| 1. Paying homage to pioneers. |

| 2. Giving credit for related work (homage to peers). |

| 3. Identifying methodology, equipment, etc. |

| 4. Providing background reading. |

| 5. Correcting one's own work. |

| 6. Correcting the work of others. |

| 7. Criticizing previous work. |

| 8. Substantiating claims. |

| 9. Alerting researchers to forthcoming work. |

| 10. Providing leads to poorly disseminated, poorly indexed, or uncited work. |

| 11. Authenticating data and classes of fact -- physical constants, etc. |

| 12. Identifying original publications in which an idea or concept was discussed. |

| 13. Identifying the original publication describing an eponymic concept or term as, e.g., Hodgkin's disease, Pareto's Law, Friedel-Crafts Reaction, etc. |

| 14. Disclaiming work or ideas of others (negative claims). |

| 15. Disputing priority claims of others (negative homage). |

Where Was this Paper Cited?

While we can discuss many sophisticated uses of Citation Indexes, there is one simple lesson in citation consciousness you should learn from my talk. No matter where you have encountered a reference--whether in a recent article, book, or conversation or in VINITI�s Referatvnyi Zhurnali --one of the Citation Indexes can tell you if that paper or book has been cited. Regardless of the year that the paper or book was published, the SCI permits you to learn where that publication was cited. Whether you use the on-line, CD-ROM, magnetic tape, or printed version of the SCI, you can locate recent papers that have cited the particular paper or work which you encountered somewhere...somehow.

I have had to cover a lot of ground in a short time. All of this is by way of introduction. The proof of the pudding is in the eating so now let us proceed with a live demonstration of retrieval by the ISI citation indexing system.

The Citation Network Maps on DNA and Ion Transport illustrate how maps help to visualize developments in science at the micro level. However, by using techniques of co-citation clustering, we can also create maps at a higher level of aggregation beginning with the global map #1. Note that it includes a category labeled Plant and Animal Genetics.

On Map #2, we see the clusters for plant and animal genetics which includes a large cluster of papers on Animal Mitochondrial-DNA.

On Map #3, Mitochrondrial-DNA goes down one more level and includes a cluster on Evolution,

FIGURE #24-3. Mitochondrial-DNAamong which is Drosophila-Melanocaster.

Map #5 is at the lowest level and identifies a series of interrelated core papers including one by Russian scientists at the Vavilov Genetics Research Institute in Moscow.

I have brought with me a floppy disk which contains a database which includes all Research Fronts in which Russian scientists are involved.

OPTIONAL

History

While the first proposal for the SCI was made in 1955, it was in the 1960s that ISI applied for and received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to create a Genetics Citation Index. As a result of this multidisciplinary project, we published the first SCI (covering the 1961 literature) in 1963. We then went on to launch a quarterly service that

eventually proved successful. Since then we have indexed the literatureback to 1945 and now the CD-ROM version of SCI is updated monthly and the on-line and magnetic tape versions are updated weekly.

In 1973, we made SSCI available. It now covers the social sciences literature back to 1956. The index deals with topics such as anthropology, economics, sociology, educational research, and information sciences among other fields.10A&HCI was introduced in 1978. A&HCI provides access to disciplines as varied as archaeology, linguistics, philosophy, musicology, literature, and others in the arts and humanities.11

Advances in modes of access have also been made over the years. In 1974, the SCI became one of the first large-scale databases available on-line via DIALOG. Other ISI databases followed. In 1988, SCI (and later SSCI and A&HCI) became available on CD-ROM. This new technology and increased data storage capabilities enabled us to implement a variety of access and browse features unique to our citation-based searching. Enhancing the power of citation searching through bibliographic coupling, you can navigate the literature by exploring papers that share one or more references. 12

OPTIONAL

KeyWords Plus

KeyWords Plus is called derivative indexing because the terms are derived from the titles of articles cited in the article being indexed.KeyWords Plus augments traditional key word or title retrieval to a varied extent -- anywhere from 10% to over 100%. For example, using Current Contents on Diskette®, you can search on an article such as "The spectrum of autoimmune thyroid disease with uticaria" from Clinical Endocrinology, and find that the key words UTICARIA, VASCULITIS, THYROID DISEASE, and HASHIMOTO THYROIDITIS are expanded to include the additional KeyWords Plus terms ASSOCIATION And ANGIODERMA. Again, the user is the ultimate filter. When KeyWords Plus is used in a weekly or monthly file, as with Current Contents®, you can readily filter out the noise from the music. On the other hand, doing an annual search may require further refinement, as mentioned above, by combining one or more words and cited references since you would expect to find 52 times as many references.

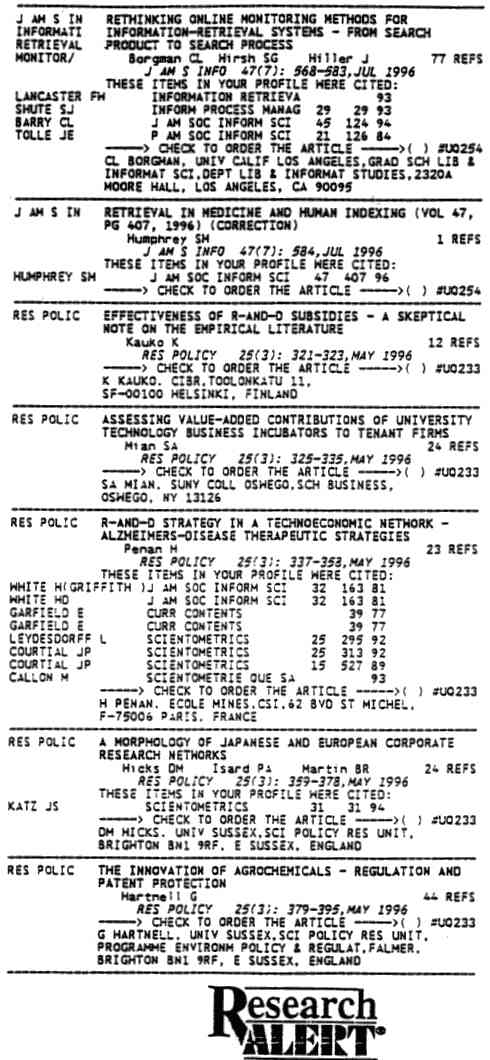

Research Alert®

As an extension of that principle, you can also take advantage of what today is called "Push Technology." In a recent letter I sent to theNew York Times,13 I pointed out that ISI, provided the first system for push technology over 30 years ago. This is a weekly service called Research Alert. Through this customized alerting service, used by many Russian scientists including Victor Vaskovsky, they are informed of articles written by colleagues throughout the world which cite their work. A search profile, consisting of a list of key references that symbolize your interests, is matched against the reference profiles of about 20,000 new articles that ISI indexes each week. The result is what I like to call systematic serendipity--unpredictable but relevant discoveries.

In my own case, I regularly learn about 15 or 20 articles per week published in journals I normally do not receive or see in the library or in the course of my normal journal reading.

FIGURE #25 : RESEARCH ALERT EXAMPLE In my latest Research Alert here are a few papers I�ve chosen to read.

In the same way, you can use the SCI monthly or quarterly to provide your own personal alert to identify, who has cited any author or work in which you have an interest. This is a unique feature of citation indexing which should be more widely used.

References:

1. back to text Merton R. K. Foreword. (Garfield E)Citation indexing--its theory and application in science, technology, and the humanities. Philadelphia: ISI Press, p. vi (1983).

2. back to text Kochen M. "How do we acknowledge intellectual debts?" Journal of Documentation 43:54-64 (1987).

3. back to text Urey H. C. "Lifelike forms in meteorites." Science 137:623-8 (962).

4. back to text Selye, H. "General adaptation syndrome," Journal of Clinical epidemeology 6, 117, 1946.

5. back to text Gray W. A. & Harley A. J. "Computer assisted indexing," InformationStorage and Retrieval 7:167-74 (1971).

6. back to text Garfield E. & Sher I. H. "KeyWords Plus--algorithmic derivative indexing," Journal of the American Society of Information Science 44:298-9, (1993).

7. back to text Geer, B. "Unusual Citings: Journal citation integrity and the public services librarian," RQ 35(1):67-73 (Fall, 1995).

8. back to text Wouters, P. "The Signs of Science," Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the International Society for Scientometrics and Informetrics. Jerusalem: The School of Library, Archive and Information Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pgs. 491-504 (1997).

9. back to text Garfield E. "When to Cite," Library Quarterly 66(4):449-458 (October, 1996).

10. back to text Garfield, E. "The new Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) will add a new dimension to research on man and society. Current Contents® (31) May 1972. (Reprinted in: Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: ISI Press, 1977. Vol. 1. p. 317-9).

11. back to text Garfield, E. "Will ISI's Arts and Humanities Citation Index® revolutionize scholarship?Current Contents (32): 8 August 1977. (Reprinted in Essays of an Information Scientist, 1980. Vol. 3. p. 204-8.)

12. back to text Garfield, E. "Announcing the SCI Compact Disc Edition: CD-ROM gigabyte storage technology, novel software, and bibliographic coupling Make desktop research and discovery a reality. Current Contents (22): 30 May 1988. (Reprinted in Essays of an Information Scientist, 1990. Vol. 11. p. 160-70.)

13. back to text Garfield, Letter to the Editor, New York Times, in press.