www.eugenegarfield.org

|

Francisco

Ayala has

had a long and productive career which we are here to celebrate. While my colleague Dr. Pudovkin can provide

some perspective on Ayala from the viewpoint of a population

geneticist, my

personal perspective is that of an information scientist. My insight is

based on my long experience in

using bibliographic databases, both for information retrieval as well

as

research evaluation. I approach the

problem of evaluating scientists from the perspective of a science

librarian

who might be asked “What can you tell me about this fellow F. J. Ayala?”

The

first step in this process is to determine what Ayala has published. Of

course, you can do that by consulting his

C.V., if it is available. Alternatively,

you can obtain a list of his publications

by

searching

public databases like PubMed or Medline. If you search PubMed

or Medline,

you will find only 220 papers by Ayala indexed. However,

if you do the same author search in

the Science

Citation Index, you will

find initially that he has published at least 320

papers. The discrepancy is

due to Medline’s

somewhat narrow

definition

of

biomedical research and its selective coverage of multi-disciplinary

and life science journals. Consider that some of Francisco’s earlier

publications appeared in the journal Ecology which is outside the realm

of Medline.

Furthermore, neither Medline nor SCI will tell

you directly

whether Ayala has published books. However, as will be seen, the SCI

cited reference section reveals all the non-journal works he has

published – at least those that have been cited at least one time, as

e.g. his 1980 book, Modern Genetics, co-authored with J.A. Kiger.

The cited reference section of SCI on the Web of Science tells you where Ayala has been cited. You get an immediate impression of a highly productive scientist who has published in dozens of journals and a variety of fields. In fact, over 500 articles and books by Ayala were identified. We know from long experience that only a small percentage of authors publish that many. That would be characteristic of a member of the National Academy of Sciences, or as I have often phrased it – a scientist of Nobel class. However, publication counting is often suspect. There are authors who publish a lot but are rarely cited and vice versa. We do know that Nobel Prize winners publish six times the average author and are cited at least 30 times the average.1,2 So we want to know not only how much a scientist has published but also whether they have published in high impact journals. And in particular, we want to know the citation impact each paper has made since impact factors of journals alone can be deceptive. For that, the SCI is ideal. We can easily identify those papers that have been cited with unusual frequency. It is noteworthy that while most of Ayala’s papers have appeared in high impact journals, one of his most-cited papers appeared in Evolutionary Biology which at the time it was published, wasn’t yet indexed by SCI. Nevertheless, citations to it can be found. To answer the question “What

do we know about Ayala?,” we can

now say that among his hundreds of papers, a relatively small group

have made a significant citation impact. This does not mean that his

less-cited work is not significant but it would require a more

subjective understanding of the works in question to make that

judgment. It is not unusual that an author will say that some of his or

her most interesting papers were not cited much. But I can assure you

from 40 years of experience that it is rare that a scientist of “Nobel

class” has not published one or more papers that can be defined as a

“Citation Classic.”

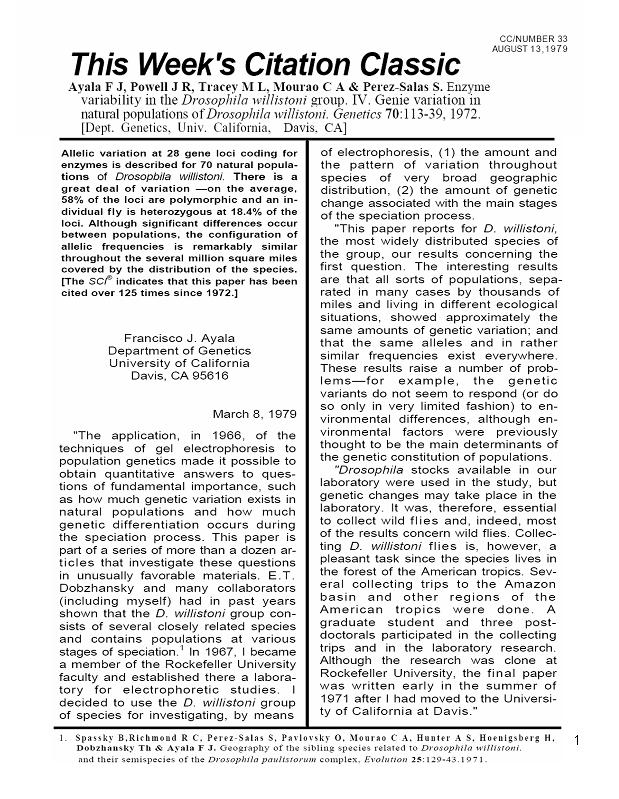

Ayala is no exception. FIGURE 1: AYALA CITATION

CLASSIC From here on, I will leave it up to Dr. Pudovkin to elaborate on the detailed bibliometric characteristics of Ayala’s work and also provide you some qualitative statements about these works. Part of his analysis is aided by a program called HistCite that he and I developed together over the past several years.3 HistCite helps readers overcome the problem of information overload, and aids scholars in creating a visual perspective of the key papers and shows their historical connection. This visualization is called an historiograph.

Our analysis will provide a series of tables produced by the HistCite program after the source records for Ayala’s papers have been retrieved from the Web of Science, which is the Internet version of the Science Citation Index and available today at most universities in the world. The database on which our

analyses are based comprises not only

the 6000 or more papers that have cited Ayala’s work but also

identifies the dozens of other key authors and “outer” works that have

been co-cited and thereby, they contribute to the historical

development of his work. Consider that the 6000 citing papers also

co-cited While it is interesting to obtain the global bibliometric statistics of Ayala’s work over a 40-year period, it will be more instructive to segment the analysis using several of his most-cited works. So we created separate HistCite databases which permit a microanalysis of these works, such as in his work on speciation as well as his work on parasitic protozoa. In the short time available

for this presentation, we will

focus on the highlights of the various data compiled about Ayala’s

work. The main HistCite

files from which our analyses are derived are

publicly available at my website at the University of Pennsylvania:

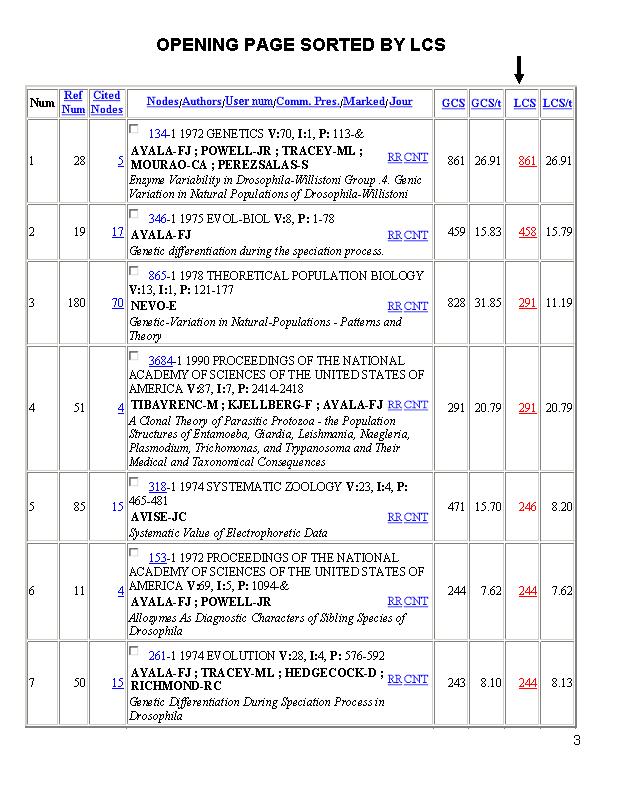

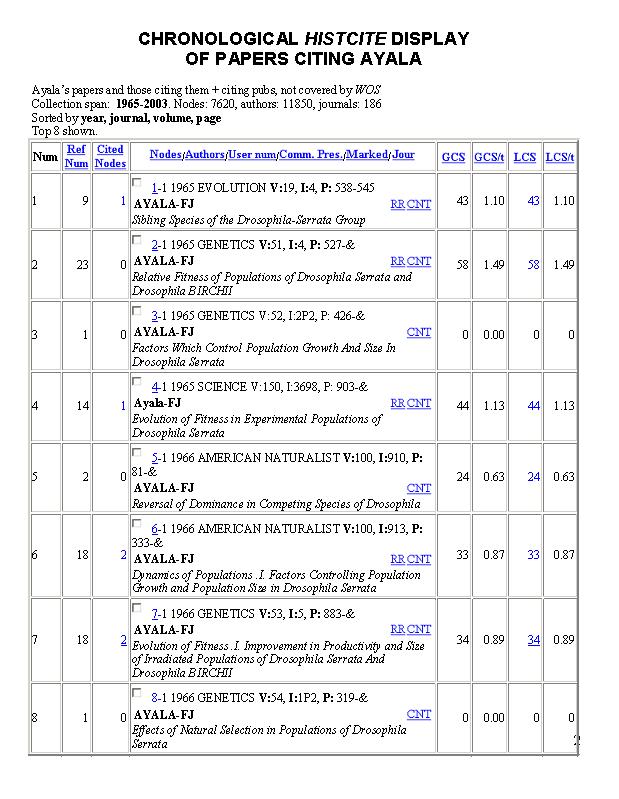

http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/histcomp/index-ayala.html . FIGURE 2: CHRONOLOGICAL HISTCITE DISPLAY OF PAPERS CITING AYALA  Figure 2 provides a view of

the opening page showing how the

information is displayed in HistCite.

This database, which we will call

for brevity the “Ayala collection” includes 7620 entries consisting of

330 of Ayala’s papers and books as well as 7290 additional papers that

had cited them by September, 2003. From these data, one can obtain a

global view of Ayala’s work and its impact over a 40-year period. For

each published paper, we can hotlink to both local and global

frequencies of citation (LCS and GCS). Note that there were 11,850

authors involved in articles which appeared in 1186 different journals. FIGURE 3: OPENING PAGE

SORTED BY LCS

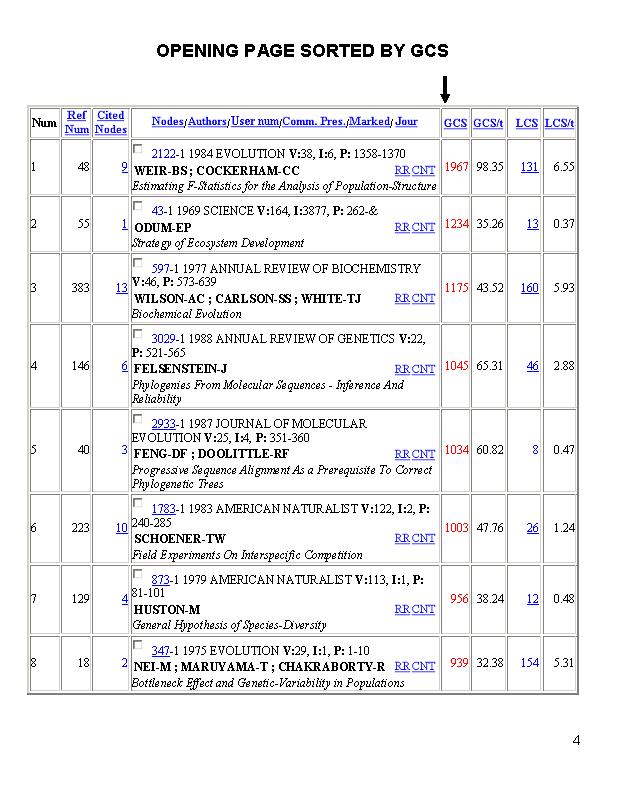

In Figure 3, one sees the most-cited papers in the collection, including mainly Ayala’s papers though there are papers by other authors as well, such as well-known reviews by Nevo, 1978 and Avise, 1974. FIGURE 4: OPENING PAGE

SORTED BY GCS

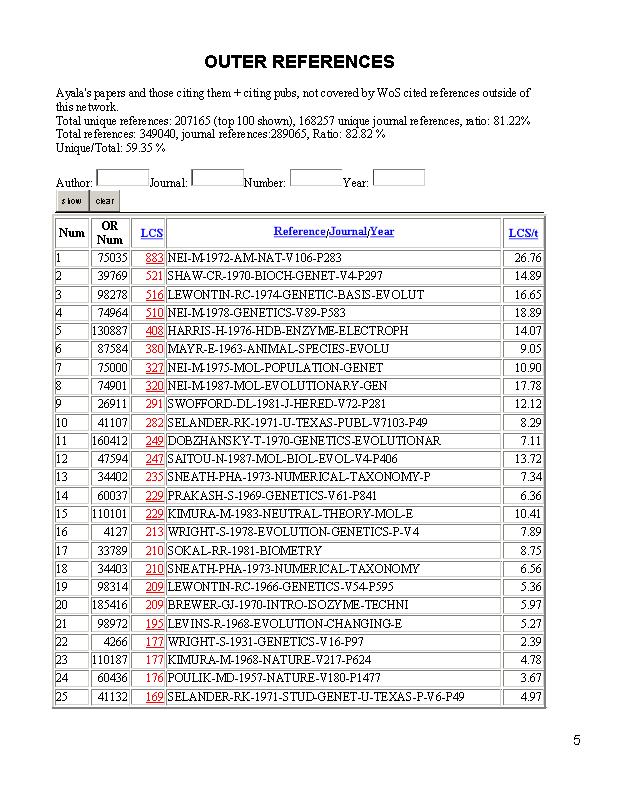

In Figure 4, we show the papers sorted by global citation frequency, that is cited by any of the 6000 journals covered by WoS. In this way, one sees that the group of citing papers includes a large number of highly-cited papers we would describe as citation classics. Here one finds the well-known paper by Weir and Cockerham, 1984 on F-statistics, and the seminal paper by Odum, 1969 on ecosystem development. The latter paper is less relevant to the local collection in which it is cited only 13 times. In contrast, the Weir paper was cited 131 times. Well-known reviews by Wilson and Felsenstein are also identified. FIGURE 5: OUTER REFERENCES  Here we see what other works are highly cited by the 7620 papers of the Ayala collection. “Outer References” are works cited by the papers of the collection but are not members of the citing collection itself. The 1st paper listed is Nei’s 1972 paper on genetic distance, then follows the compilation of gel staining recipes by Shaw, 1970. The 3rd is the well known book by Lewontin, 1974. Books by Mayr and Nei follow. Below that we see Swofford’s note on his still widely used software package BIOSYS. Thus, looking through this list one sees the works that are the backbone or foundation of the collaboration. They are in fact the list of works that were most often co-cited with papers by Ayala. FIGURE 6:

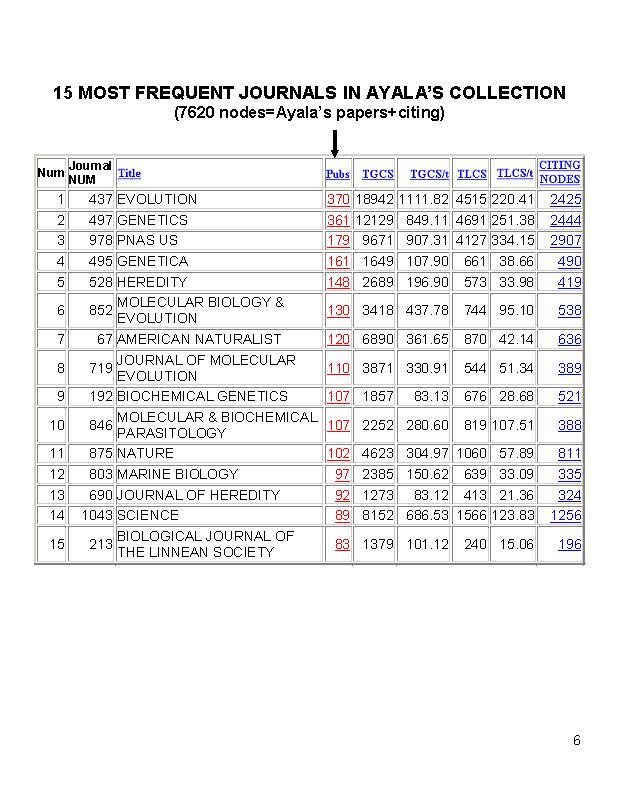

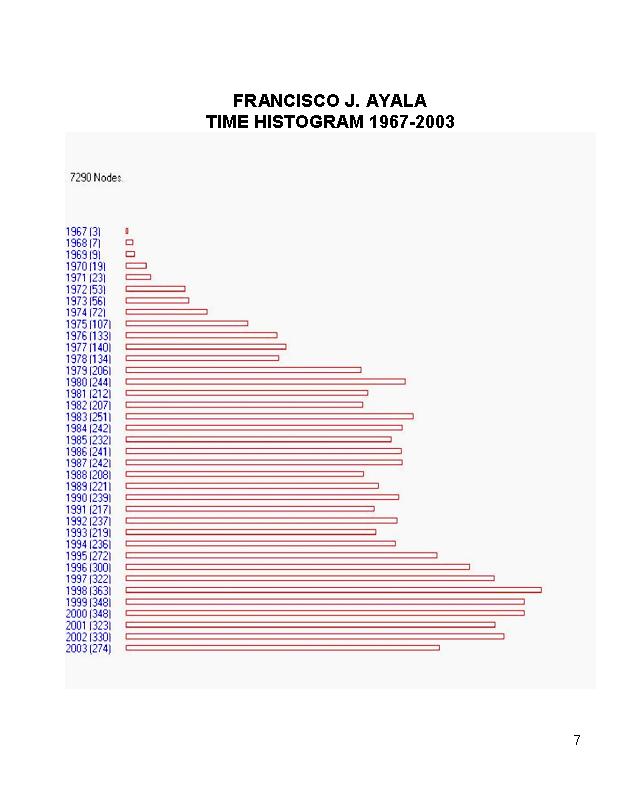

JOURNAL LIST  In Figure 6, we get a glimpse of the huge number of journals in which these citing papers have been published, some 1200 in all. The most important journals for this field of evolutionary genetics are obviously Evolution and Genetics. PNAS, Genetica, Heredity, etc. also published many papers. FIGURE 7: TIME HISTOGRAM  Figure 7 provides a chronological histogram of citations to Ayala’s works, demonstrating that citation frequency grew steadily from 1967 (2 years after his first publications in 1965) to 1980, when it reached a maximum of 244 citations. From then to 1993 yearly citation frequency remains at the same level of about 240. From 1993 the frequency grows again reaching the maximum of 363 per year in 1998. FIGURE 8:

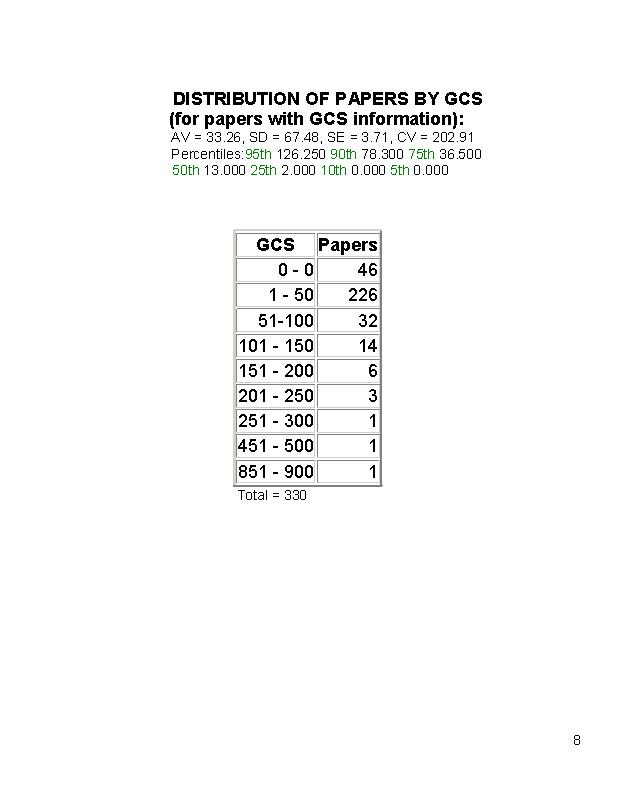

DISTRIBUTION OF CITATION FREQUENCIES OF AYALA’S WORKS Figure 8 presents

the distribution of global citation frequencies of Ayala’s

publications. Of the 330 papers, 26 were cited 100 or more times, and

12 were cited 150 or more times. To put this in perspective,

approximately .1% of all papers ever cited were cited 100 or more

times. About half as many were cited 150 times.

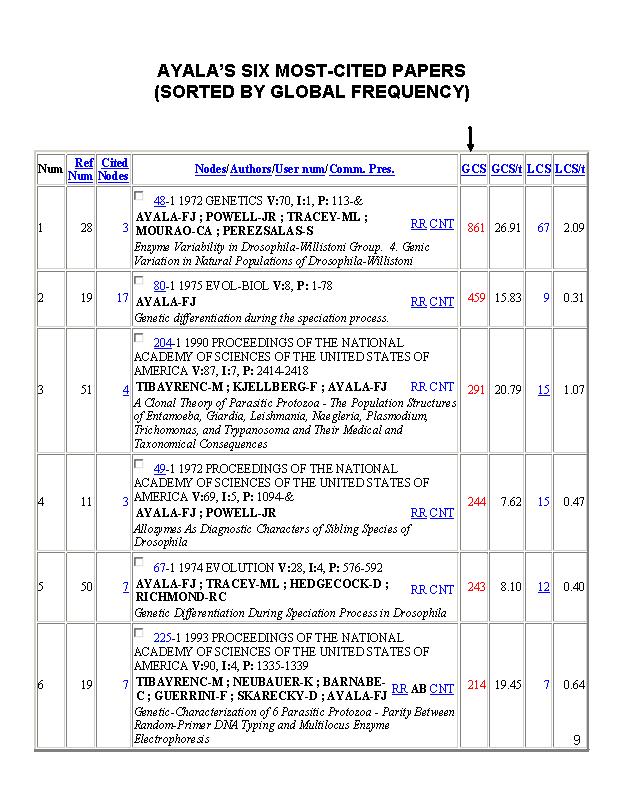

FIGURE 9: AYALA’S SIX

MOST-CITED PAPERS

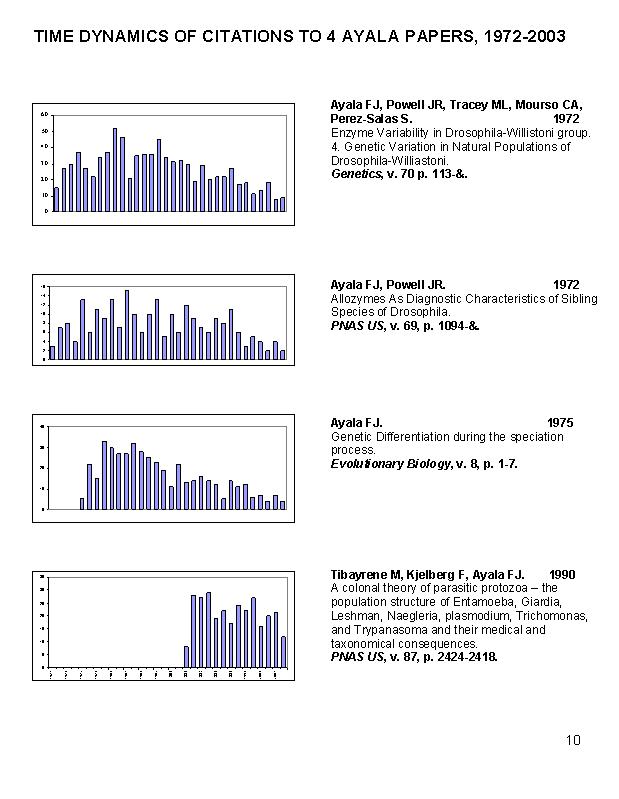

Ayala’s six most cited publications are shown in Figure 9. These papers were published from 1972 to 1993, with citation frequencies ranging from 214 to 861. Four of them are dedicated to Drosophila allozyme genetics and differentiation during speciation process, two deal with genetics of parasitic Protozoa. Ayala’s citation classic of 1972 on genetic variation in Drosophila willistoni seems to be the first large scale study of allozyme genetic variation, involving thousands of individuals from different and distant parts of the geographic area of the species genotyped at many allozyme loci. It strongly argued in favor of selectionist understanding of ubiquitous intraspecific molecular genetic variation. Though the paper in Evolution, 1974 was cited much less intensively, it seems to me to be Ayala’s masterpiece, clearly and convincingly describing genetic changes during speciation. This theme was further elaborated in a highly cited review in Evolutionary Biology, 1975. The 1990 and 1993 papers showing clonal population structure in parasitic Protozoa were regularly and frequently cited about 20 times a year after their publication. FIGURE 10: TIME DYNAMICS OF

CITATIONS OF 4 AYALA’S PAPERS

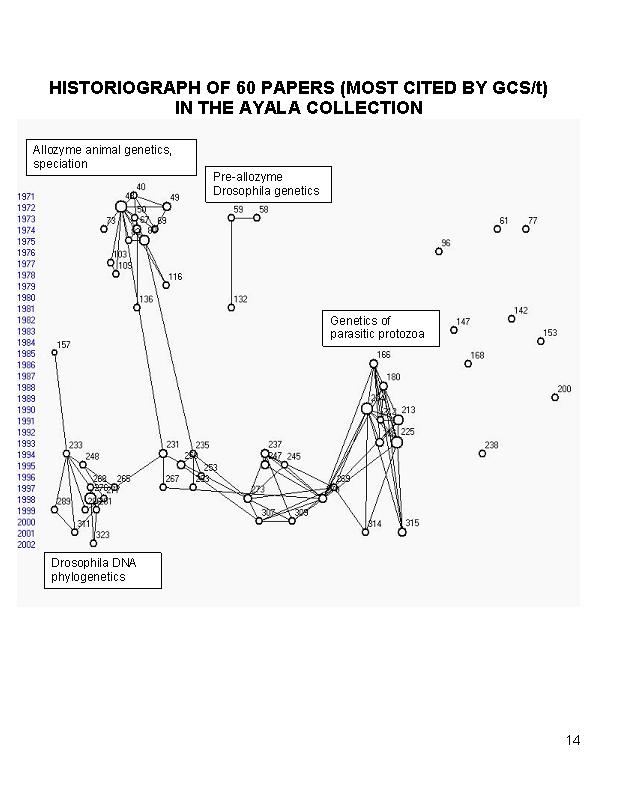

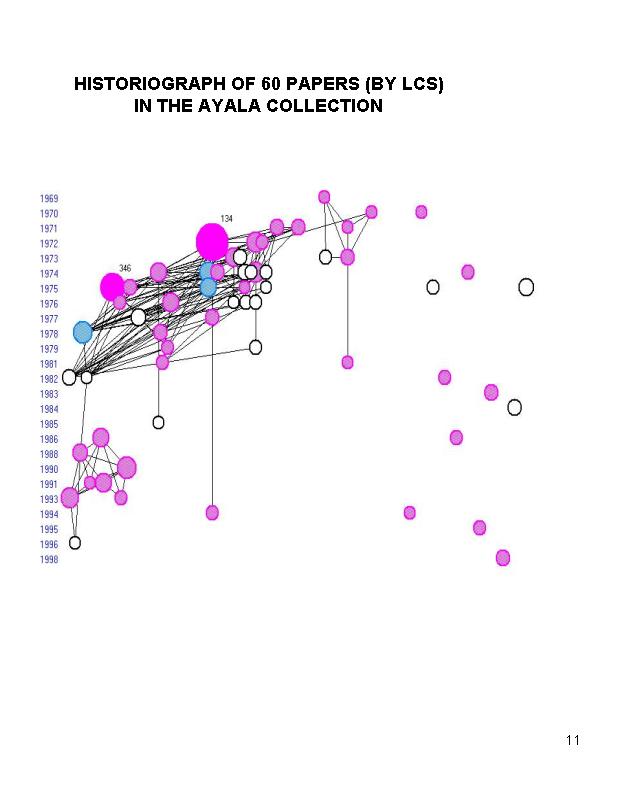

FIGURE 11: HISTORIOGRAPH 60

PAPERS

(BY LCS) IN THE AYALA COLLECTION  In Figure 11, we have generated an historiograph of the 60 most-cited papers in the Ayala collection. Each paper is denoted by a circle, the area of which is proportional to the citation frequency of the paper. The vertical axis gives the publication year, the horizontal axis is rather arbitrary, though proximity on it reflects citation linkages of papers, which are indicated by straight lines. Ayala’s papers are shown in purple. The majority of the papers (39) are by Ayala and his co-authors (they are highlighted). The two most-cited of Ayala works include his citation classic of 1972 in Genetics (#134) and his review on genetics of speciation in Evolutionary Biology, 1975 (#346). Ayala’s papers are tightly linked to papers of other authors, among which are the highly cited papers by Avise (Systematic value of electrophoretic data. Syst.Zool, 1974), King and Wilson (Evolution at 2 levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science, 1975), the well-known review by Nevo (Genetic variation in natural population. Theoret. Pop. Biol., 1978). The citation frequency of Ayala’s works when compared to the citation frequency of co-cited papers illustrates the importance and impact of Ayala’s research. FIGURE 12: HISTORIOGRAPH OF

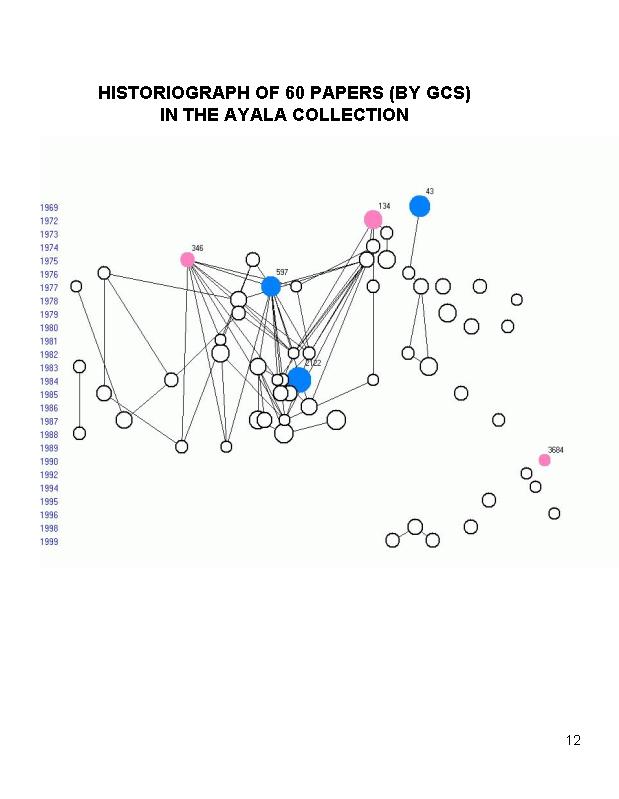

60 PAPERS (BY GCS) IN THE

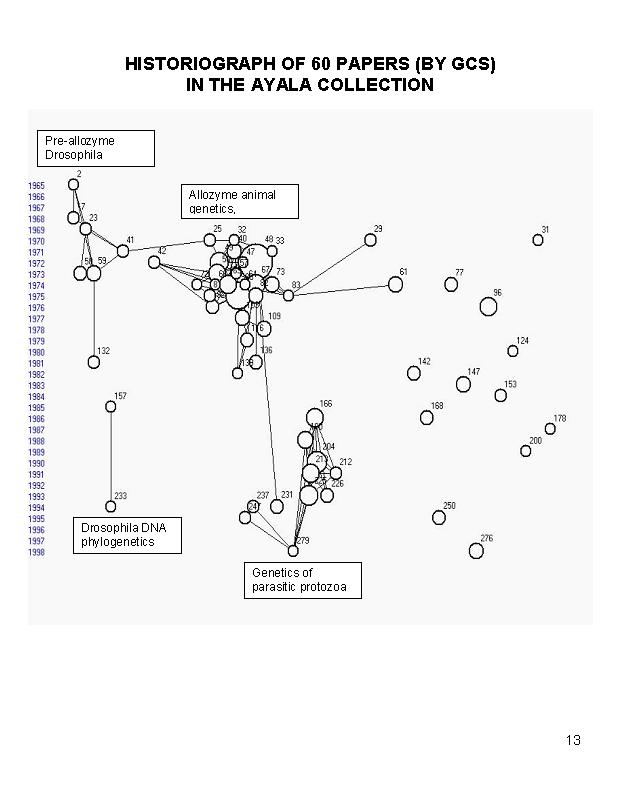

AYALA COLLECTION  Figure 12 similarly shows the most globally cited publications in the same collection. Ayala’s 3 most cited works of 1972, 1975, and 1990 are shown in purple. Other works shown (in blue) are the well-known papers by Odum (Strategy of ecosystem development. Science, 1969, #43), Wilson, Carlson and White (Biochemical evolution. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 1977, #597), Weir and Cockerham on F-statistics (Evolution, 1984, #2122). FIGURE 13: HISTORIOGRAPH OF

AYALA’S 60 MOST

CITED PAPERS ( GCS)  Figure 13 displays the 60 most-cited papers by Ayala himself (the minimal citation being 49). On the right one can see papers that do not cite and are not cited by other papers of the graph. These are either books or book chapters, globally highly cited, though not citing other papers in the graph, or they represent highly cited papers by Ayala on philosophy or religion, which happen not to cite any other papers in the graph. One can also see 3 groups or clusters of papers connected with citation links – group of papers in the upper left corner (2,7, 23, 58, 59), large upper central group around Ayala’s most cited paper (48), the group in the lower central part of the graph (166, 180, 204, etc.). The first cluster mostly includes papers of the pre-allozyme era. The second (and the largest) cluster includes papers on allozyme genetics in different animal groups and the speciation process, mostly in Drosophila. The 3rd cluster consists of papers on genetics of parasitic protozoa. It is interesting to note there is little intercitation between the clusters. Actually, the 3rd cluster is not citation-linked to the 1st or 2nd clusters at all. One may see that the most recent papers displayed in Figure 13 are of 1998. To make more recent papers visible, we selected 60 papers with the highest per year citation rate, rather than overall citation frequency. FIGURE 14:

HISTORIOGRAPH OF AYALA’S 60 MOST CITED PAPERS ( GCS/t)

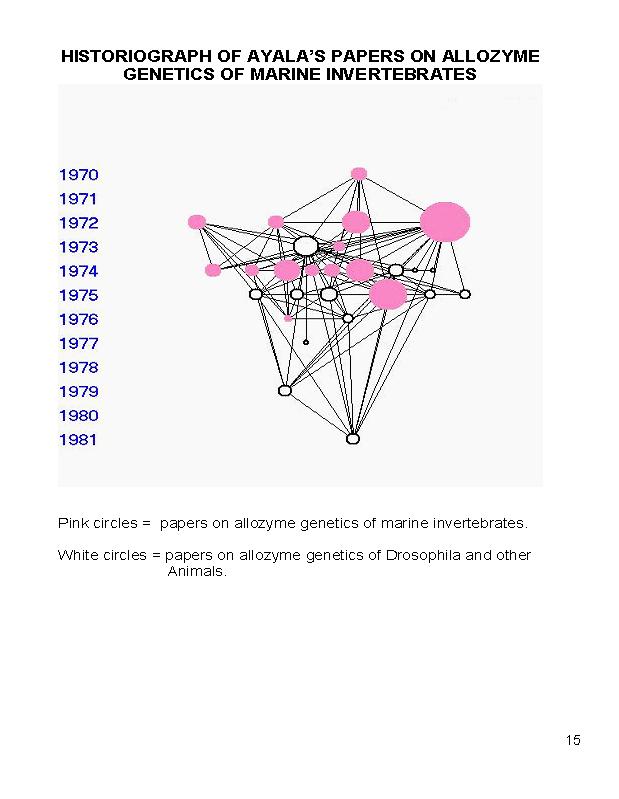

They are presented in Figure 14. While in the previous figure the publication years of the papers were from 1965 to 1998, in Figure 13 the range is 1971 to 2002. Cluster 1 has almost disappeared; only 3 papers are left of it (58, 59, 132). Cluster 2 is less numerous, but still quite visible. More important, new clusters showed up. Cluster 4 (157, 233, 248, 265, 268, 276, 277, 281, 286, 289, 311, 323) is in the lower left corner of the graph. In the previous figure only 2 papers of this cluster were visible (157, 233). This cluster consists mostly of papers on evolution of SOD locus in Drosophila and on molecular clock. To the right of the 4th cluster there is a group of papers (let’s call them 6th cluster: 231, 235, 250, 253, 263, 267)), weakly linked to the 4th and 2nd clusters and more strongly linked to the adjacent group of papers (5th cluster: 237, 247, 273, 307, 309). The 5th cluster is strongly linked to the 3rd cluster, which is now larger than in the Figure 13 (4 papers are added to it: 269, 279, 314, 315). The 5th cluster consists of papers on malaria parasite and is understandably linked to the 3rd cluster, which includes papers on other parasitic protozoa. Thus, our analysis revealed 4 main foci in Ayala’s research: pre-allozyme Drosophila studies (cluster 1), allozyme genetics of different animal species and the speciation process in Drosophila (cluster 2), genetics of parasitic protozoa (cluster 3), Drosophila phylogenetics, based on DNA sequences, and molecular clock (cluster 4). Of course, there are other topics covered in Ayala’s research. For instance, allozyme genetics of marine invertebrates. FIGURE 15:

HISTORIOGRAPH OF AYALA PAPERS ON ALLOZYME GENETICS OF MARINE

INVERTEBRATES

Ayala’s 13 papers on allozyme genetics of marine invertebrates (cluster 5) are blended with cluster 2. Open circles are papers on marine invertebrates, pink-colored circles are of Cluster 2. FIGURE 16: INFORMATION ON

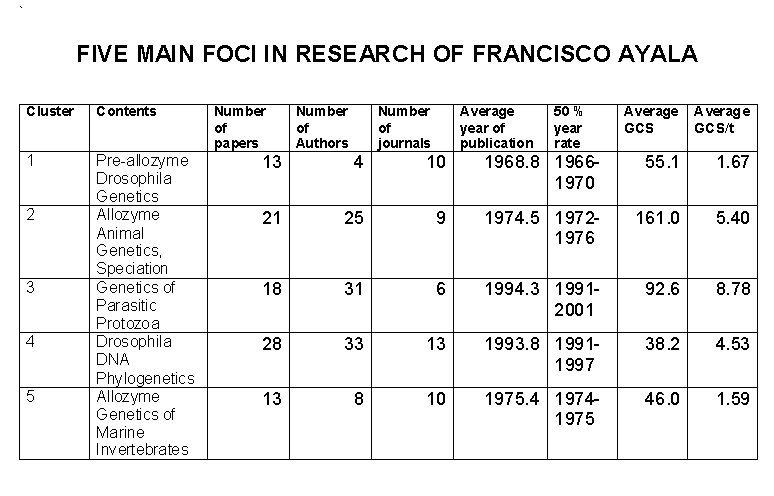

AYALA RESEARCH FOCI

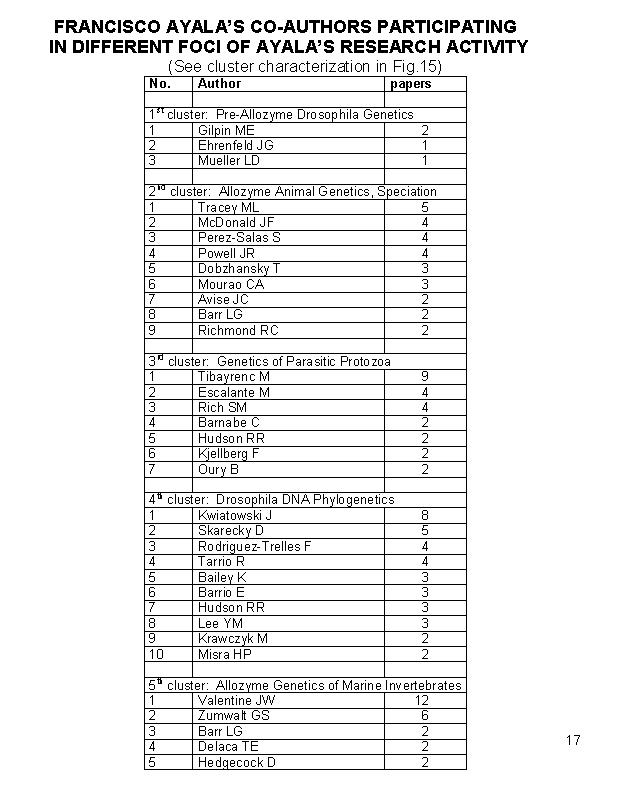

Figure 16 characterizes the 5 Ayala research foci. As noted before, clusters 2 (allozyme genetics and speciation) and 5 (marine invertebrates) overlap in time. Papers of the “marine invertebrates” cluster were published during a rather short period: 50% of them were published within 1974 and 1975. Research on genetics of parasitic protozoa (cluster) and on DNA Drosophila phylogenies (cluster 4) also overlap in time, but they are much longer than the previous clusters. The most cited groups of papers involve cluster 2 (allozyme Drosophila genetics) and cluster 3 (population genetics of parasitic protozoa), the average citation frequency per paper being 161.0 and 92.6, per year citation frequency being 5.40 and 8.78. The 4th cluster (labeled “Drosophila DNA phylogenies”) has been cited much less, 38.2 citations per paper or 4.53 per paper per year. FIGURE 17: AYALA’S

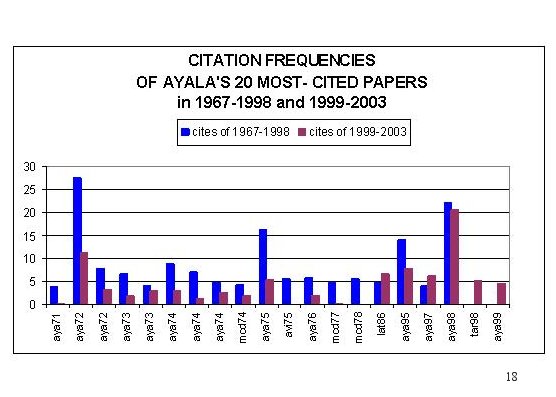

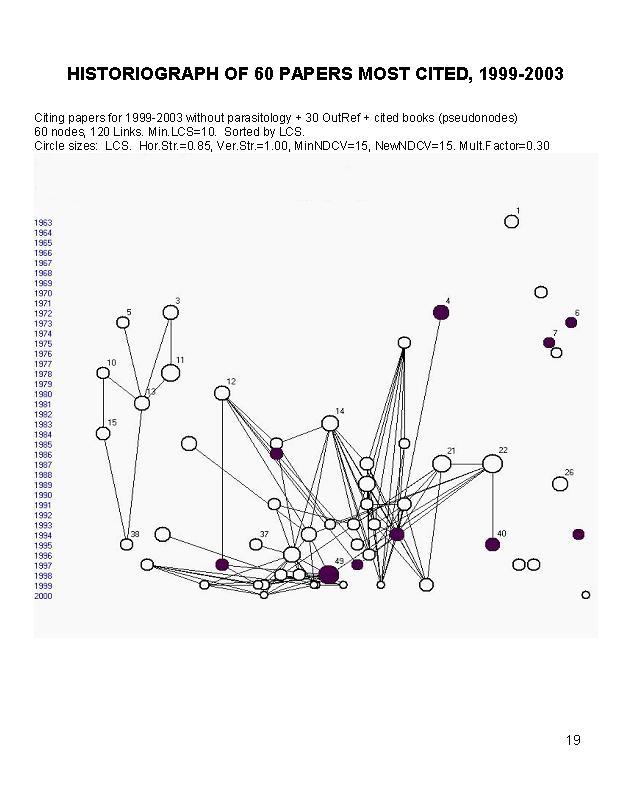

CO-AUTHORS  Figure 17 should remind Francisco of his co-authors in different periods of his career (the people shown here, co-authored in two or more of Ayala’s papers within the corresponding cluster). It is noteworthy that membership in each of the clusters does not overlap -- with 2 exceptions: RR Hudson participates in the 3rd and 4th cluster and LG Barr in the 2nd and 5th clusters. If we took into consideration all co-authors, including those with only 1 paper within a cluster, the overlap would be somewhat greater. As Ayala’s papers on genetics of parasitic microorganism seem to be rather unlinked to his other papers, we decided to split the main collection of citing papers into two subsets: those citing Ayala’s “parasitology papers” and all the rest. FIGURE 18: CITATION FREQUENCIES OF AYALA’S 20 MOST-CITED PAPERS Figure 18 shows per year citation frequencies of Ayala’s 20 most-cited papers (in the non-parasitology set) in1967-1998 and in 1999-2003. The majority of these papers are cited in both periods, though papers published after 1986 are cited more in later years. Interestingly, the paper by Ayala, Rzhetsky and Ayala, Jr. (PNAS US, 1998) on the origin of the metazoan phyla and molecular clocks was highly cited just after it appeared and it continues to be well cited till now -- more than 20 citations per year. FIGURE 19: HISTORIOGRAPH OF

60 PAPERS MOST LOCALLY CITED

IN 1999-2003  To show how Ayala’s work stands on the shoulders of his predecessors, we added the 30 most-cited Outer References of this non-parasitology bibliography to the collection. Figure 19 maps the 60 most locally-cited papers of this non-parasitology bibliography. Ayala’s papers are in black. One can see that Ayala’s papers are well integrated into the network of other frequently cited papers on evolutionary genetics (which constitute this non-parasitology file). A cluster of papers in the left of the graph are theoretical works describing new numerical methods (Nei, 1972, 1978; Sneath, 1973, Wright, 1978) and software packages implementing them – BIOSYS (Swofford, Selander, 1981), GenePop (Raymond, Rousset, 1995). FIGURE 20: AYALA’S OWN

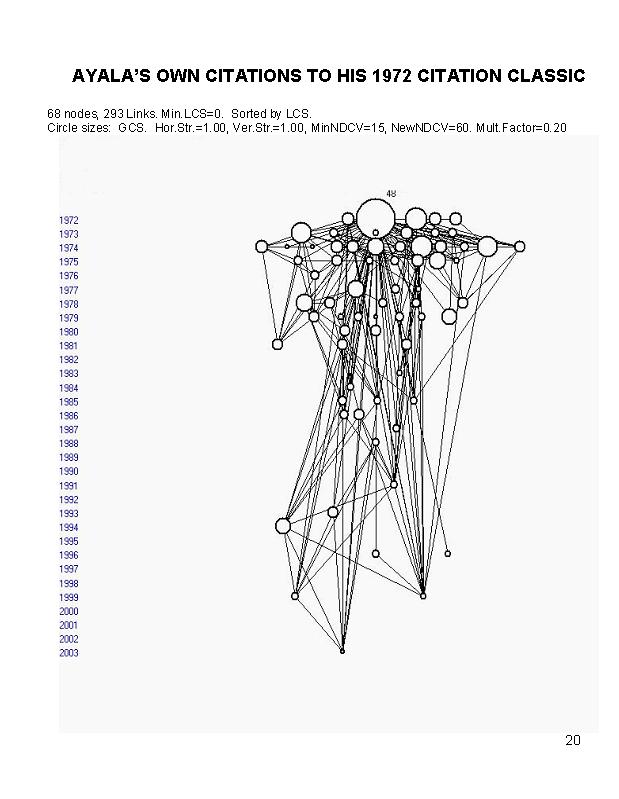

CITATIONS TO HIS CITATION CLASSIC OF 1972  One characteristic feature of Ayala’s work is recurrent attention to the problems he investigated earlier. We mentioned that his work on different problems often was done in parallel: while intensively working on genetics of parasitic microorganisms after 1986 he worked on molecular phylogenies in Drosophila. Figure 20 shows Ayala’s own citations to his most cited work on allozyme genetic variation in Drosophila willistoni (Genetics, 1972). He cited this paper in 67 of his own papers, the latest one in 2003. Thus, he has been returning to the subject regularly since 1972.

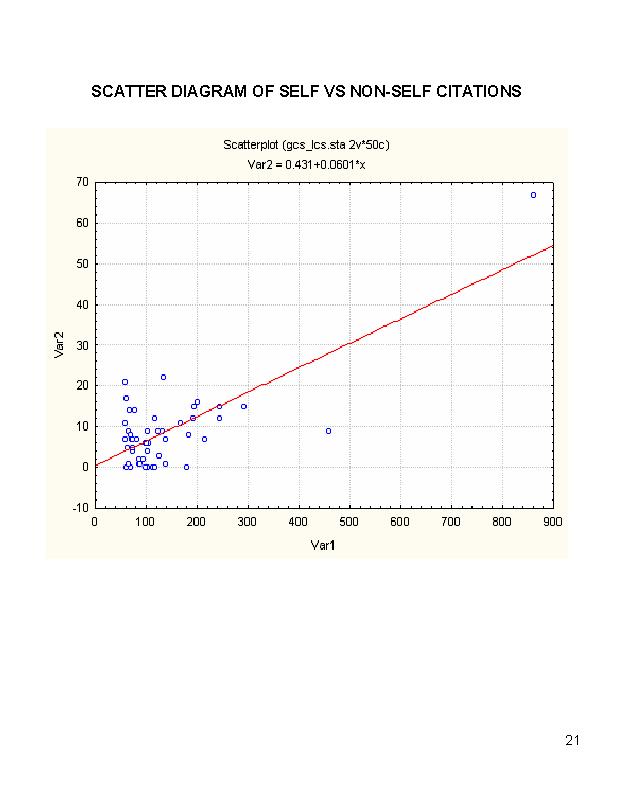

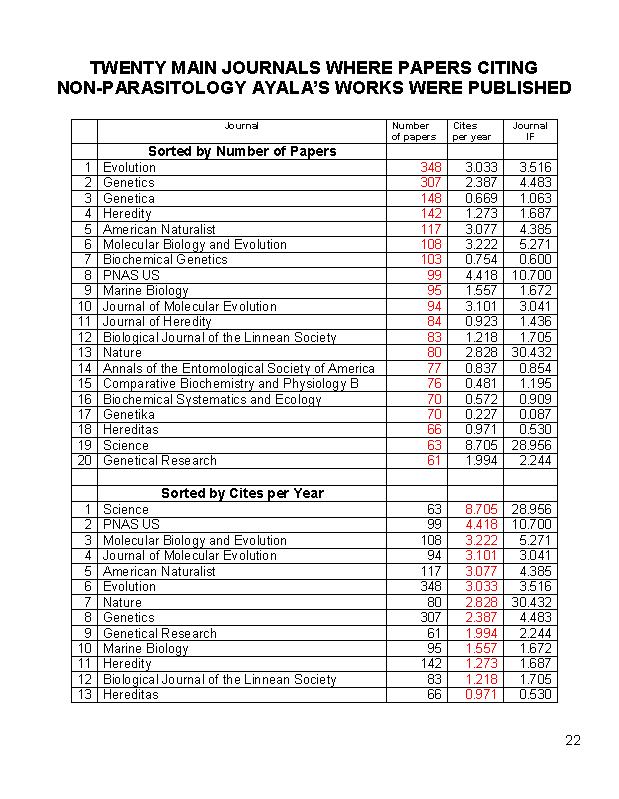

It seemed interesting to us to see how Ayala’s own citations to his papers correlated with citations to the same papers by other authors. In other words we wished to determine if the author’s judgment of his papers agrees with the attention of other authors (measured in citation rate). Figure 21 shows a scatter diagram illustrating the point. One may see there is a rather strong correlation (r=0.757) between the numbers of Ayala’s own citations to 50 of his most cited papers and citation frequencies to the same papers by other authors. Though it is clearly seen that this correlation is mostly created by two of his most cited works (of 1972 and 1975) if we remove these 2 works, the correlation becomes much weaker: r=0.301. We may conclude from this that significance of a paper for the author himself and its value for other people may be different. FIGURE 22: CITATION

FREQUENCIES OF

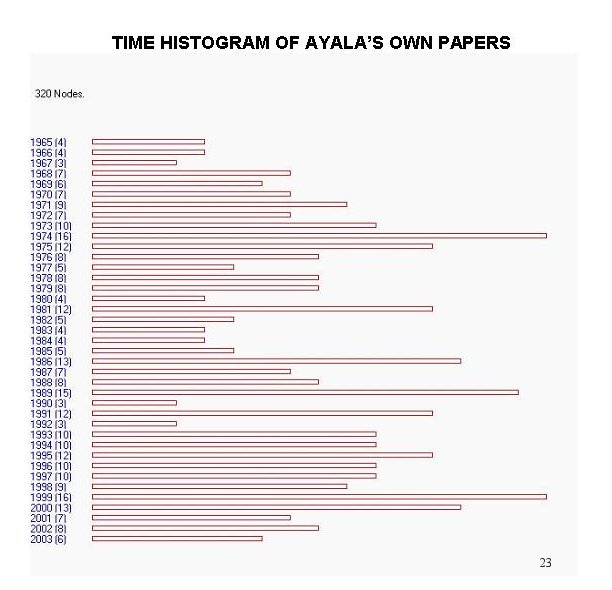

PAPERS IN DIFFERENT JOURNALS  Figure 22 gives citation rates of the papers of the non-parasitology citing set published in different journals. The table gives the information on the 20 journals most important for the field of evolutionary genetics. Understandably, the highest number of papers is published in Evolution, then Genetics, Genetica, Heredity. It seems interesting that of 115 journals listed in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) category of Genetics & Heredity only a limited number publish papers on this topic. And many of these journals are not of high impact, e.g. Genetica (IF=1.063), Biochemical Genetics (0.600), Hereditas (0.530), Genetika (0.087). Rather unexpected for us was the discrepancy between the journal impact factor (IF) and average citation frequency of papers of this data set for some journals. The most striking discrepancy, as shown in the bottom table, was the citation rate of papers in Nature: while the IF for Nature is 30.432, the average per year citation rate for 80 papers published in it was only 2.828. The citation rate of 348 papers published in Evolution was even higher than that (3.033), though the IF for Evolution is only 3.516, much less than for Nature. FIGURE 23: TIME HISTOGRAM OF AYALA’S OWN

PAPERS  Thus, we arrive at the following

conclusion: Francisco Ayala is a prolific author, who has been

publishing about 7 papers per year over his 40 year career. More than

40% of Ayala’s publications are in high impact journals (within top 10%

- PNAS, Genetics, Evolution). Many of his papers have been highly cited

over a long period, and continue to be highly cited, some of which

reached the status of “citation classic”. During his career Ayala

worked in different subfields of population and evolutionary genetics

and in each of them he produced highly-cited works. His students and

co-authors exceeded 200, and many of them also produced highly cited

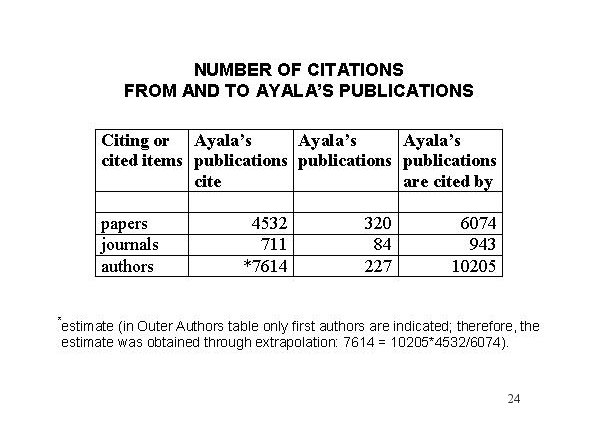

publications of citation classic rank. FIGURE 24: BIBLIOMETRIC SUMMARY OF AYALA’S PUBLICATIONS  Figure 24 gives a bibliometric summary of

Ayala’s publications: 320 of his papers that were included in WOS were

published in 84 journals. They were co-authored by 227 people. Ayala’s

320 papers cited 4532 other papers which were published in 711 journals

and authored by 7614 people, and were cited by 6074 papers which were

published in 943 journals and authored by 10205 people. References: http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/papers/onrpaper.html 2. Garfield E. and Welljams-Dorof A. "Of Nobel Class: A citation perspective on high impact research authors ," Theoretical Medicine 13(2):117-135 (1992). Reprinted in Essays of an Information Scientist, Volume 15, pages 116-136.Philadelphia: ISI Press (1993) http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v15p116y1992-93.pdf http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v15p127y1992-93.pdf 3. a. Garfield E, Pudovkin AI, Istomin VS. "Why do we need Algorithmic Historiography?" Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 54(5):400-412 (March 2003). http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/papers/jasist54(5)400y2003.pdf b. Garfield E, Pudovkin AI, Istomin VS. "Algorithmic Citation-Linked Historiography -- Mapping the Literature of Science," Presentation at : ASIST 2002: Information, Connections and Community, 65th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science & Technology (ASIS&T). Philadelphia, PA. November 18-21, 2002. http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/papers/asis2002/asis2002presentation.html Abridged version in Proceedings of the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science & Technology (ASIS&T), Vol: 39, p.14-24, November 2002. http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/papers/asist2002proc.pdf |