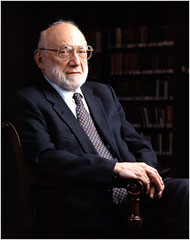

Joshua Lederberg, 82, a Nobel Winner, Dies

By WILLIAM J. BROAD

Published: The New York Times, February 5, 2008

Joshua Lederberg, one of the 20th century’s leading scientists, whose work in bacterial genetics had vast medical implications and led to his receiving a Nobel Prize in 1958, died on Saturday. He was 82 and lived on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

Rockefeller University, where Dr. Lederberg was university professor and president emeritus, announced his death on Monday, saying the cause was pneumonia.

A prodigy as a youth, Dr. Lederberg was 33 when he won the Nobel for Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and exchange genes. He was one of the youngest Nobelists, sharing the 1958 prize with Edward L. Tatum and George Beadle for their discovery at Stanford in the 1940s that genes act by regulating specific chemical processes.

Dr. Lederberg’s discovery that bacteria engage in sex created new understandings of how bacteria evolve and acquire new traits, including resistance to antibiotic drugs. A founder of the field of molecular biology, he helped lay the foundations for many biological revolutions, including biotechnology.

Dr. Lederberg moved in diverse worlds. A brilliant analyst and visionary, he led early inquiries into the possibility of computer intelligence, theorized about alien life in distant galaxies and advised American presidents for a half century. He also wrote a weekly newspaper column, “Science and Man.” His ideas were often decades ahead of the conventional wisdom.

He was also a dedicated educator, working in administrative posts at the University of Wisconsin, as well as at Stanford and Rockefeller and taking an interest in helping and developing young scientists.

“He was a very broad ranging, open-minded, curious scientist who loved to look into new territory and find scouts who would come with him to explore,” said David A. Hamburg, a president emeritus of the Carnegie Corporation and past president of the Institute of Medicine in Washington. “That was the pattern of his career.

“He was one of the great scientists of the 20th century. I know that’s a strong statement, but it’s justified.”

Donald Kennedy, the editor of Science magazine in Washington and a former colleague of Dr. Lederberg’s at Stanford, said that on Dr. Lederberg’s arrival at the school nearly a half century ago, “he was already a hero, the most important founder of bacterial genetics and microbiology.”

Dr. Lederberg was born May 23, 1925, in Montclair, N.J., to Zvi Hirsch Lederberg, a rabbi, and the former Esther Goldenbaum, who had emigrated from what is now Israel two years earlier. His family moved to the Washington Heights section of Manhattan when he was 6 months old.

After graduating from Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan in 1941 at 15, he went to Columbia and studied zoology, receiving a bachelor’s with honors at 19. He then went to medical school at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia.

In 1943, he enrolled in a special Navy medical training program, working at St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens, examining servicemen returning from war in the Pacific for parasites that cause malaria.

After two years in medical school, in the summer of 1944, Dr. Lederberg transferred to Yale and helped pioneer the field of bacterial genetics. He received his doctorate at Yale in 1947.

At the time, scientists believed that bacteria reproduced asexually by dividing into genetically identical halves. But Dr. Lederberg found that bacteria possessed a genetic mechanism, called recombination, similar to that of higher organisms, including humans.

It began with the transmission of genes from one bacterium to another.

Dr. Lederberg left Yale in 1947 for the University of Wisconsin, where he continued to study bacterial genetics. He broke administrative ground by founding the department of medical genetics, helping doctors modernize their often outdated approach to disease.

At Wisconsin, he also helped prove that genetic mutations occurred spontaneously, confirming a long-held belief of evolutionary studies.

Dr. Lederberg was elected to membership in the National Academy of Sciences in 1957 and was made a charter member of its Institute of Medicine.

In 1959, he joined the Stanford School of Medicine, where he was chairman of the department of genetics and was a professor of biology and computer science, working on research in artificial intelligence, biochemistry and medicine.

In 1978, he moved to Rockefeller as its fifth president, serving until June 1990.

Regularly shuttling to Washington throughout his life, Dr. Lederberg advised a total nine White House administrations, according to Rockefeller University. On Dec. 15, 2006, in a White House ceremony, President Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Dr. Lederberg began his federal advisory career in 1957, when he joined President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Science Advisory Committee, a panel of several leading scientists. The panel worked on nuclear arms control and other security questions.

From 1966 to 1971, Dr. Lederberg wrote a weekly column for The Washington Post, commenting on science education, scientists’ role in society and divisive topics like population control, intelligence testing and regulating recombinant DNA technology.

In a 1968 column, he accused policy makers of “blindness to the pace of biological advance and its accessibility to the most perilous genocidal experimentation.” In 1972, at Washington’s urging, most nations renounced germ warfare as immoral and repugnant.

Something of a wordsmith, Dr. Lederberg coined the term exobiology, or the study of the possibility of alien life. He collaborated with the astronomer Carl Sagan in establishing exobiology as a scientific discipline and in educating the public on the biological implications of space exploration.

With the dawn of the space age, his warnings about interstellar contamination and his call for the scientific study of life beyond Earth’s atmosphere tapped into popular fascination and brought him international attention.

One account holds that Dr. Lederberg argued that the first astronauts returning from the Moon should spend weeks in quarantine — earning their fury — because of his worry that they might inadvertently import alien microbes.

Among Dr. Lederberg’s many positions was being a member of the Advisory Committee for Medical Research of the World Health Organization. He was also elected a foreign member of the Royal Society, London; an honorary life member of the New York Academy of Sciences; and an honorary fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine. In 1989, he received the U.S. National Medal of Science.

The National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Md., has a sampling of his thousands of papers, letters and articles on a Web site, the Joshua Lederberg Papers at http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/BB/.

His first marriage, to Esther Lederberg, ended in divorce in 1966; a microbiologist, she was a member of her husband’s research team in the early 1950s, and was credited with discovering a virus that invades bacteria and hides within its DNA, often emerging later to destroy its host. Dr. Lederberg is survived by his wife, Dr. Marguerite S. Lederberg; two children, Anne of New York, , and David Kirsch of Chevy Chase, Md.; and two grandchildren.

From the start of the space age, Dr. Lederberg was fascinated by the possibility of extraterrestrial life. He long advised NASA on how to operate its probes to avoid contaminating foreign bodies with terrestrial microbes, as well as accidentally bringing alien ones back to Earth.

“He wanted NASA to take every safeguard,” Dr. Hamburg recalled. “They took him very seriously.”